I’ve always been a “what if” kind of person, much to the chagrin of my husband who, for all purposes, is practical and very much a realist. As one of many dreamers in this world, I can honestly say that we consider all the “what-ifs.” We ponder all the possibilities, we think outside the box every time. Which makes sense, considering we tend to be idealistic and creative people – our thought processes are typically profound and somewhat abstract.

We’re the people who make decisions with our hearts just a little more than with our brains. We can easily be driven by emotion over logic, thus, we are easily hurt. Also? Dreamers, by nature, really dislike conflict; we much prefer harmony. Indeed, we will often push our needs to the absolute bottom in order to maintain group harmony. Conversely, if it involves issues we consider paramount to our moral fiber, we will not be silent or complacent for the sake of harmony. For those, we will compose a symphony of discord to be understood – or at least, heard.

My dad is a fellow dreamer, and I’m happy to have another one in my life. Being married to a realist can be lonely at times, because I have no one to consider all the “what ifs” with. I suppose being a dreamer married to a realist is actually a pretty good balance, because he keeps me grounded. In fact, it’s probably a great thing I didn’t choose to spend the rest of my life with another dreamer, because I imagine we’d live on a perpetual loop of “what ifs” and would never get anything productive accomplished.

Dad holding me while I slept, summer 1974

June 5th marked Matt’s and my anniversary (18 years married, 21 years together). We don’t do much fanfare anymore – just heartfelt or funny cards, sometimes a dinner out. We always watch our lovely wedding video that Dad made and gave us, and I still cry over that every year. But we’re at that point in life where the notion of doing *nothing* is very seductive, and we’re more likely to choose that over being out & about, dealing with a toxic mix of social anxiety, claustrophobia, and the general public. This upcoming fall, we have tickets to see one of our favorite authors, David Sedaris. That will be our anniversary gift to each other.

Despite it being my anniversary month, I consider June my Dad’s month. Because it marks both his birthday (June 2nd), and Father’s Day, which is upcoming in a few days. While these are only two dates on the calendar, they represent two of the many times throughout the year in which I purposefully reflect on my dad’s influence on my life. As a fellow dreamer, we share lots in common. But one thing always loved exclusively by my Dad was trains. Everything trains. Trains in real life, toy trains, model train sets of all scales, train movies, train decor and themes, and train magazines. He even pretended to love the tacky train kitsch I gave him for birthdays and father’s days when I was very young. A 99-cent toddler-sized wooden train whistle with the carved inscription I Like Trains for a 45-year-old man? Yes! A baseball cap reading This is my train and you can’t play with it for a man who never wears baseball caps? Sure!

For this hobby, everywhere we lived Dad would carve out a niche somewhere in the cubbyholes and name it “the train room.” In the 1960s before I was born, I understand the train room was in a dark, dank, underground basement lit by a couple of dangling, pull-chain lightbulbs overhead and a bank of camel crickets tenanting every corner. In the house where I spent the majority of my time growing up, the train room first was situated in a long, odd-shaped, abandoned walk-in closet off the upstairs hallway. Later, it was central to a small room addition that he and my mom constructed near the back of the house.

When they eventually retired and built a house on some quiet, country pond property, the train room was located outside the house, a short walk away. It was inside a generous barn-like shed that stood among their forest of pine trees – pine trees that were ultimately unearthed in 1996 by Hurricane Fran. That train room was perhaps my favorite, with my dad’s heating unit cranked up to high in the winter. It made the space inviting and cozy, especially if you had some hot coffee.

It was here one late fall evening after dinner where I found Dad contentedly watching over his model trains, our sweet, faithful dog Max resting at his feet, and a third item that did not belong – a Harvestman, (or Daddy-Longlegs), hitching a ride on a miniature boxcar as it circled the track. Without speaking, I looked from this “spider” back to my Dad, my eyes squinted tightly with furrowed brow. As if this was an occurrence one should expect to see, Dad explained that these “spiders” (which weren’t even spiders, technically) were friendly, harmless, and most importantly, didn’t like the cold, and that they regularly came in and kept him company when it got too brisk outside.

“But why is it riding around on your train?” I asked. Dad answered as if it were common sense, “Because that’s what he likes to do! I welcomed him in. He’s happy; let him be!” Next I’m fairly certain Dad referenced scripture from the book of Matthew along the lines of “…truly I tell you, whatever you have done unto the least of these, you have done unto me.” Subtext: though this arachnid may seem insignificant to you, it is still one of God’s living creatures and I feel charged to take care of it by whatever means necessary.

I understood this language. This particular bible verse was one persistently declared by the kids in our household to justify the frequent bringing home of feral cats when Mom opposed, so I understood immediately; there was no need to argue. And then I thought, one day when Dad is no longer with us, I hope and pray to always remember him exactly this way – in his happy place, mellow, leaning back in his chair, pipe between his teeth, cold beer in hand, content dog resting at his feet, a man quietly enjoying the beauty of his creation. A moderate, liberal, loving man who felt empathy and emotions so deeply, that he always made sure to care for ‘the least of these.’“

Aside from being a place of comfort and refuge for all, the train room was also an unexpected sort of art studio. It was the place where my Dad imagined, planned, designed, engineered, and used his bare hands to build amazingly intricate model train layouts (HO scale is what I mostly remember, but he used all scales at different times). He would often start out with a plain plywood door as the benchwork on top of whatever supporting structure was there. From there he would build upwards, from the terrain and landforms, to the working hanging stoplights over the town.

One of the very few photos we have of one of Dad’s many different scaled model train set layouts; he painted or placed every decal with precision

Carved, extruded foam became the hill and mountain profile, or sometimes, just wrinkled brown paper grocery bags, stuffed with crumpled newspaper held in place with masking tape. With an artist’s precision, he’d brush on earth-color latex paint for dirt surfaces, or cover the terrain with liquid or spray pigments and all sorts of textured surfaces. He could blend and combine colors that rivaled nature’s own. What an adept eye he had.

After weeks or sometimes months of hard work, when completed, Dad’s train sets included fantastically brilliant scenes of ordinary, every day life, often with some humor infused: bustling towns with tiny people interacting, the “town drunk” was usually hanging out with a stray cat among store fronts or back alleys, and little passengers seated inside little passenger train cars appeared to be going somewhere besides the perpetual loop they were on. There were sparkling rivers that seemed to rush, level crossings, paved roads with potholes and hand-painted center stripes, different levels of vividly colored underbrush and autumn foliage, and lush, undulating meadows.

Dad painstakingly added every detail around and on every building, from the paint colors, to the decals, to the graffiti on the bench, with teeny, tiny paintbrushes, and a ton of patience

No attention to detail was lost, regardless of how time-consuming they may have been to create. Weathered galvanized roofs of boxcars, Aging freight car lettering that was fading, or running onto the paint below, decals meticulously applied with tweezers on every building and speed-limit or billboard sign, graffiti, rusted water tanks, working electrics, lighting, special effects, and the landscapes. My God, the landscapes; they were way more realistic and beautiful than even the prize-winning photographs inside Model Railroader Magazine, the only reference point for this art form I had at the time.

Then, without warning, one day I’d walk in the train room to ask Dad a question, and the entire layout would be completely obliterated. Demolished. Gone. Not a trace of the artistry was left behind except maybe an edge of blue horizon paint on the wall. And then he’d start from scratch, all over again, and build another, totally different layout. Another trip to The Hobby Shop, another theme, another scale, more wiring and soldering, more needlenose pliers, hobby knives, Testors enamel paint, foam insulation, and plastic bags of fine terf, green poly fiber, and medium ballast.

I’d wonder, “why do all that hard work just to tear it down? Did it get boring? Did you not like the way it turned out? Why not at least take a picture of it first, for preservation? What is this whole process chasing after? At the time, I simply couldn’t make sense of it all – the way this man, who was my Dad, had the artist’s eye of John Constable and work ethic of Alexander Graham Bell just blew my mind. How come I didn’t inherit that talent or dedication? I longed for it.

When I was pretty young, mostly between the ages of five to ten, my dad would take me lots of different places in general (to school, to his workplace during the summer, to friend’s houses, to the Quick-Pick up the road where I’d try his patience deciding which candy bar to buy this time), but one of the places we went most often for fun was downtown, to the city’s train station – usually during the summer, on Friday nights near dusk.

One of my very young trips to see a train, in Zebulon. My grandmother is holding me on the left, Dad is on the right. He was filming a news story.

We’d visit early before the train was scheduled to arrive and we’d walk up and down the railroad tracks, picking up and studying various railroad remnants like rusted metal spikes and tattered ticket stubs. Occasionally we’d come across casual small objects that might’ve fallen out of someone’s suitcase, now buried underneath a layer of gravel and dust, long forgotten. We’d suppose what kind of person might’ve owned that thin leather wristwatch, or where they were traveling, or what their story was.

The type of rusted metal spikes Dad & I would pick up along the railroad tracks

Although I just thought we were having fun, these trips were also very educational. My dad would teach me about the history of railroads in America as well as other countries, and I learned how railroads reflected the times they operated in, and vice versa. I learned that railroads were economic entities, not just cool places to hang out and people-watch on Friday nights. I learned how trains moved raw materials and manufactured goods from place to place, and how the patterns of these movements were all driven by economics. My Dad taught me the different types of trains, specific train stations (and sometimes, their ghost stories), and the characteristics of different types of railroad cars like freight, passenger, sleeper, lounge, and cargo. I learned about how engines work, why railroad tracks went one or the other, what whistle codes, hand signals, and different light signals meant, and I learned about geography, landforms, bridge construction, and tunnels.

Train tracks in downtown Raleigh, circa 1981. Source: http://www.pwrr.org

During our walks up and down the tracks, waiting sometimes what seemed like hours for the train to arrive, I’d ask lots of my notorious “what if” questions. One I remember in particular was a “what if” I asked after learning about the function of a railroad switch and how it enables a train to be guided from one railway track to another. My dad was telling me about the strength of the switch motors and how railway workers had to be careful to keep their limbs out of the way, and I wondered what might happen if a person was walking along the track and their foot suddenly got ensnared when the switch motor was engaged.

I’m sure he gave me some technical answer about the likelihood of that actually happening, or possibly glossed over gory details of how that would likely crush and break all the bones in one’s foot, but I don’t remember exactly what he said. I was too busy thinking, “wait a minute… what if that person was me, and what if it happened right now while I’m walking with you? And what if there was no one around to help?” I asked him this out loud and his answer, without even a moment’s hesitation was, “Well, I guess I’d have to get out my pocket knife and cut your foot off. That’d be the only way to set you free if nobody was around to help.”

I was horrified at the thought because it was such a disturbing image, and yet, I was also mystified that someone could love me enough to go to such lengths to save my life – all within this complicated, “what if,” completely speculative and made-up scenario that my six-year-old mind concocted.

Looking back, with the perspective of now being a parent myself and having knowledge of how tiring it is to answer all the “what ifs” of little kids’ imaginations, I realize my dad probably just said the first thing that popped into his mind to placate me, so I’d quit with the “what ifs.” Or maybe because that answer was easy and uncomplicated for a six-year-old mind, and it satisfied my question so I could then move on. He knew me so well.

Later in the evening, by the time conversation had run out of steam, we’d finally hear the far-off air horn of the Amtrak Silver Star, or maybe the CSX or Seaboard System locomotive. As the sound of the Nathan Airchime approached and grew more intense, we’d back up into the safety of the train depot where we could stand and watch. As the train approached and I could feel the rush of wind, I would get butterflies in my stomach. Maybe that was just adrenaline and excitement because that massive, oddly majestic beast of steel and aluminum was finally arriving. Sometimes the freight trains would whoosh past us on their way, sometimes the Amtrak would stop at the station.

CSX, circa 1984, Raleigh, source: http://www.trainweb.org

Seaboard System, 1983, source: Don Ross Collection, Don’s Depot

Amtrak Silver Star, circa 1981, source: http://www.pwrr.org

When the train would stop, there was so much to take in: the squeal and hiss of the brakes and the faint smell of burning, the muffled announcements heard from crackling overhead speakers, the eclectic mix of people getting on and off, the clacking of luggage wheels on pavement. The shadows of people sitting in windows would prompt my mind to wonder another string of “what if” questions regarding who they were and where they were going… it was a never-ending scene of noise and movement that abruptly ended the second the train doors closed for departure.

We’d then watch the train as it inched off towards another destination, leaving more quietly than it had arrived. In the lull following its departure, the train station would resume its deserted, ghostly appearance while the dirt and dust settled. Dad would say, “Well, that’s it! Ready to head home?” And as the evening stars grew brighter we’d load back into the car, my summer feet grubby and sooty from walking bare along the tracks. He’d drive us home talking about the next time we’d come and what “souvenirs” we might find.

Whether visiting my Dad’s sacred train room where I knew not to touch anything, or taking field trips with Dad to the actual train station where I was allowed to touch everything, it was always a ritual I looked forward to. Not because I was ever a train aficionado, but because it was uninterrupted quality time spent with my Dad, doing what he loved to do, what he was passionate about, that only he truly understood. I so wanted to please him and share that passion. It was fun, but honestly, I didn’t care much about the trains.

I just liked the precious alone time with my Dad, when he was in his element, happy, enjoying that special place where the earth and modern technology collide. And ultimately, the lessons I learned from his train room artistry, and our trips to the train station became major life lessons. At the time, in my young mind I was just hanging with my Dad. But what occurred to me gradually, and at unexpected times throughout my life, was that there were so many reoccurring themes of train stations and railroads that were applicable to life.

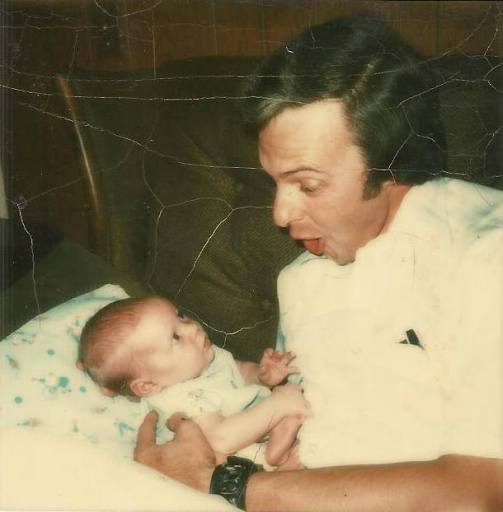

Dad, apparently trying to elicit a smile from a newborn me. July, 1974 (That bad-ass ’70s leather bracelet/watch he’s wearing, though!)

1.) The railroad track enables the train to move by providing a dependable surface for its wheels to roll upon. Life on Earth is not much different. On traditional railroad track structures, the maintenance demand is heavy and costly. Weakness of the underlying subgrade and drainage deficiencies, as an example, can lead to pretty hefty maintenance burdens and costs. Life on Earth is not much different. The earth is a fairly dependable surface for us to inhabit, at least for now. As we roll upon the course of life, we must think to take care of it. We must pay the price and invest in protecting it now so that it will remain the same solid foundation for future generations, so that they can savor and dwell upon a dependable surface as well.

2.) There’s always a diverging path. Just like with railroads, in real life there is always a choice to make of continuing along on the same path, or flipping a switch and changing your course. It is often literally that simple. If you’re not happy, change your course. A junction in the context of rail transport is a place at which two (or more) rail routes converge or diverge. In life, you might be side by side with a friend or significant other for a while before going off, forever, in two totally different directions, or vice versa. I’ve found that whichever way you end up is meant to be, whether you change your own life’s course, come together with someone new, or split ways from someone who has been at your side. However, should you happen to get stuck or ensnared somehow in the process of switching course, you most likely won’t have to lose a limb.

3.) Just like at the train station, people come and people go. You don’t always know where they’ve been, or where they’re going. You can surmise, but you might end up being wrong, or even worse, hurt. Unlike “bad order” tags applied on defective pieces of railroad equipment that are not to be used again until repairs are performed, unfortunately, our fellow humans in need of psychological repair do not come with these tags. There are, however, less obvious “red flags,” and gut feelings we have when getting into a relationship – whether friendly, romantic, sexual, or otherwise. I’ve learned to trust those red flags and gut feelings. They’re almost always as reliable as bad order tags.

4.) Don’t underestimate the importance of the “Dead Man’s Switch.” Once upon a time, if a train engineer became incapacitated in any way, there was a safety mechanism which automatically applied the brake and stopped the train. This was called a “dead man’s switch.” In most modern locomotives, an “alerter” is used. Historically, these switches and levers were intended as a fail-safe to stop a machine with an incapacitated operator from potentially dangerous action, or to stop a machine as a result of accident, malfunction, or misuse. In life, we have human counterparts of the dead man’s switch. They’re called “designated drivers.” Use them when you’re out and you’re drinking. Always. There’s invariably someone who wants to fulfill that role. If not? Call an Uber or a cab. Too many high school students, mothers, fathers, friends, relatives, and children have died in drunk driving accidents during my lifetime. It shouldn’t happen, especially when there are ways to keep it from happening.

5.) On the point of repeatedly building up and tearing down intricate model train table layouts? That thing I never quite understood? What I ultimately learned through the course of many trials and errors of my own, was that the building process was the best part. While it’s nice to sit back and admire your work sometimes, the building part is where the adventure is. Not only that, but it’s also where the learning occurs. The early years for my Dad must’ve been learning experiences because I’m sure he made some mistakes, and possibly cut corners – maybe in areas he shouldn’t have – and that maybe translated into problems that then didn’t happen the next time around.

This building & re-building theme was also evident in the house where I grew up. My parents’ idea of a fun weekend was one that included demolishing a room and rebuilding it. They were constantly re-arranging furniture and room layouts, remodeling inside and out, tearing down old walls and building new ones. The dining room turned into an extension of the living room. The TV den was turned into the dining room. They turned the kitchen around completely backwards. They put a hole in a wall to create another entrance into a room. A hallway was closed off and turned into the powder room and closet area of the master bathroom. At one point we had a patio, which later became the area for a small deck, and even later we had an English garden in the area that used to be the deck and the patio. Our house was so much in a state of flux, my friends would joke from one week to the next, “If I come over today, what part of your house will be different?”

But now I realize the bigger theme. It wasn’t just a fun adventure. My parents were always striving to make things better, to make things more cost-effective, more efficient, more aesthetically pleasing, and/or more helpful. I also learned that sometimes, tearing something completely down is the best way to move forward. Because if you don’t fully tear down something that you intend to replace, your finished product will never look or work very good. As long as my Dad was rebuilding new train tables and layouts, he was still working, improving, and learning. It was brain exercise.

Some of the more simple lessons I learned at the train station, but arguably the most important, were these:

- “What if” questions can be healthy. You might just learn a thing or two about unconditional love.

- You don’t have to spend any money to have quality time.

And lastly? Found artifacts such as the rusty metal railroad spikes Dad & I picked up along the way don’t just make great paperweights; they also trigger fond memories, bring forth an underlying wealth of random knowledge, become thought-provoking and deep conversation pieces, and as such, they make awesome souvenirs that last a lifetime.

Love this! =)

LikeLike

Wow! I didn’t know you were listening! You know more about trains than I do. Beautifully written.

I appreciate it greatly. I also enjoyed our outings. Grand daddy Mallie would take me fishing…I didn’t like to fish be he didn’t know that. I just enjoyed being with him. I love you dearly and thank you for the wonderful article.

Dad

LikeLike

Wow, Martie! A beautiful tribute to a beautiful person.

LikeLike